In recent years, mobile phones have drawn tremendous interest from the conflict management community. Given the successful, high profile uses of mobile phone-based violence prevention in Kenya in voting during 2010 and 2013, what can the global peacebuilding community learn from Kenya’s application of mobile technology to promote peace in other conflict areas around the world? What are the social and political factors that explain why mobile phones can have a positive effect on conflict prevention efforts in general?

1. A population must prefer non-violence since technology magnifies human intent

Context and intent is critical. One of the most important aspects of using mobile phones for conflict management and peacebuilding is recognizing prevailing local political climate. If a population is inclined toward peace in the midst of a tense situation, then mobile phone-based information sharing can help people promote peace and share information about potential hotspots with neighbors and peacebuilding organizations. Of course if the population has drawn lines and it ready to fight, mobile phones and make it far easier to organize violence. As Kentaro Toyama said, technology amplifies human intent and capacity. When integrating technology into conflict management and peacebuilding, the first step is to have a good idea of the population’s intentions before turning up the volume.

2. The events of violence start and stop relative to specific events

In the case of Kenya, violence erupted during particular period in the political calendar, namely during elections. Thus, violence starts and stops relative to external events, as opposed to being a state of sustained warfare. We have to be realistic about what we intend to do with the technology as it relates to peacebuilding or conflict management. In Kenya, prevention is made easier by the fact that the violence occurs around elections; the peacebuilding community has time to reach out to leaders beforehand, set up programs, test software, and organize networks of trusted reporters. It’s a different kettle of fish when violence is unrelated to something like elections, which are predictable. This starts to get into conflict early warning, where there are methodological and data challenges – we’ll be covering these in TC109, since they present some of the most interesting and difficult issues for conflict prevention.

3. The population knows to use their phones to share information about potential violence

So the population prefers peace, and we all know when violence is going to happen. Now we have to make sure everyone knows that there are people listening when text messages are sent in reporting violence, and where those messages should be sent. Training and public outreach are key to making sure there is participation in a text message-based conflict management or peacebuilding program. This has to go on even when there aren’t high risk events like elections looming. One of the best examples of this kind of training and network building is Sisi Ni Amani, a Kenya-based NGO that does SMS peacebuilding, civic participation and governance training, and conflict mitigation around land disputes. By developing capacity within communities between elections, Sisi Ni Amani helps communities be prepared to respond to, and be proactive in, peacebuilding.

4. Third party actors involved in collecting and validating the crowdsourced data.

Never underestimate the value of having a third party involved in validating and rebroadcasting the information that comes from crowdsourced SMS text messages. In situations where trust between communities may be shaky, having the United Nations or a large NGO monitoring and responding to citizen reports can lend institutional credibility to the information being shared by local citizens.

Endnote: These factors were taken as excerpts from a recently published article titled, “Inter-ethnic Cooperation Revisited: Why mobile phones can help prevent discrete event of violence, using the Kenyan case study.” To read the entire published piece in Stability: International Journal of Security & Development, including works cited, please click here.

Charles Martin-Shields is a doctoral candidate at George Mason University’s School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution. He is currently a Fulbright-Clinton Fellow in Samoa, advising their Ministry of Communications and Information Technology on disaster response and data collection. Learn more from his primary research and also from other technology-for-peacebuilding experts by enrolling today in our upcoming Technology for Conflict Management and Peacebuilding course. The course runs January 13 – February 7, 2014. Group discounts available. Please inquire at info [at] techchange [dot] org.

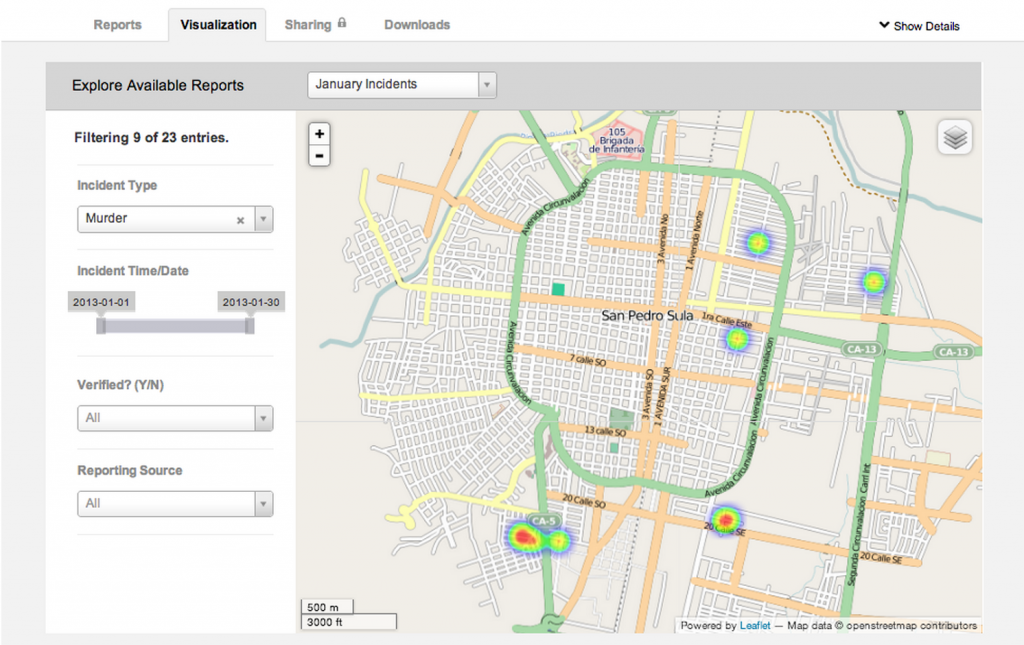

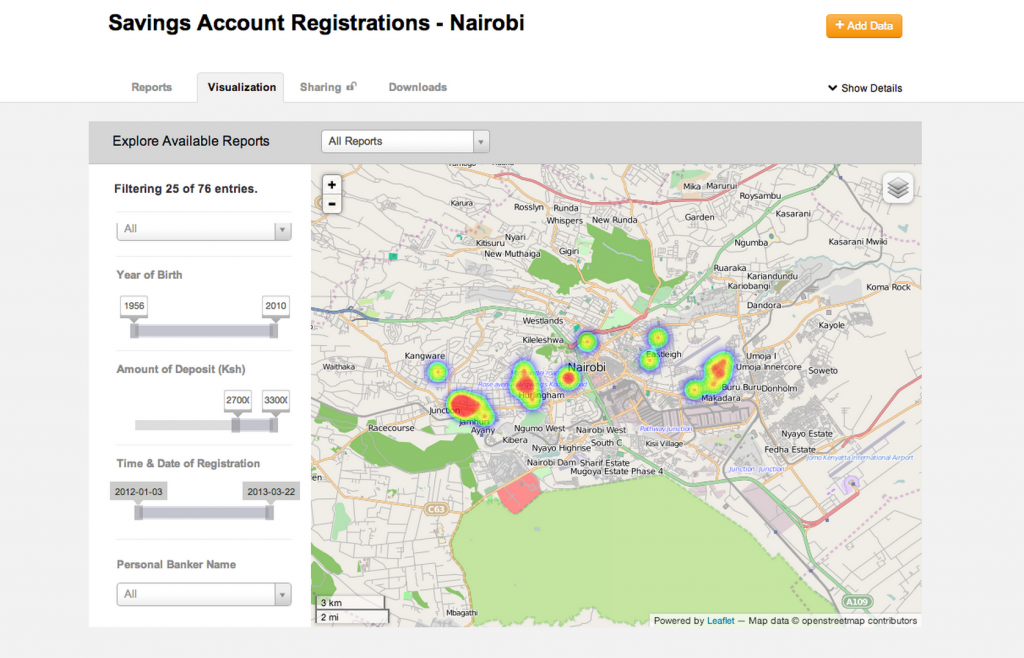

The problem of preventing violence centers of two things; predicting where violence will occur and the ability for institutions to respond. Emmanuel Letouze, Patrick Meier and Patrick Vinck lay this problem out in their chapter on big data in the

The problem of preventing violence centers of two things; predicting where violence will occur and the ability for institutions to respond. Emmanuel Letouze, Patrick Meier and Patrick Vinck lay this problem out in their chapter on big data in the