Interested in learning with us? Check out our next course on Technology Innovation and Social Entrepreneurship, starting Oct. 1. Apply now!

What does it mean in a country transitioning from a long and bloody civil conflict if almost every citizen owns a mobile phone? Can the ubiquity of mobile communication play a role in breaking-down perception barriers and promoting reconciliation between communities?

I workshopped this question last week with Sri Lanka’s largest youth movement, Sri Lanka Unites, at their 2012 Future Leaders Conference in Jaffna. The conference brought together more than 350 youth from all of Sri Lanka’s ethnic and religious communities for four days of workshops focused on building relationships and empowering students to take action to support reconciliation nationally and within their local communities.

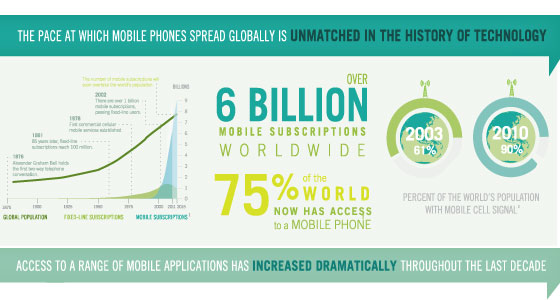

Few countries have higher mobile penetration than Sri Lanka- where 95 percent of the island nation’s population has a sim card and access to a mobile phone according to GSMA’s Mobile and Development Intelligence Unit.

Leveraging that connectivity asset for peacebuilding could be immensely valuable, particularly for country-wide civil society groups such as Sri Lanka Unites which seek to re-build relations between previously warring ethnic and religious communities through youth conferences such as FLC as well as grass-roots development initiatives.

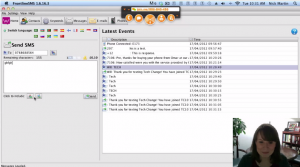

To explore the ways in which mobile and social tools could be deployed in Sri Lanka for peacebuilding and development, I spoke briefly about the evolving deployment of mobile-based tech tools such as FrontlineSMS and Ushahidi by civil society groups to assist in everything from mapping electoral violence in Kenya to supporting earthquake reconstruction in Haiti and coordinating flood relief and fundraising in Pakistan.

Myself and Chandika Jayasundara (the co-founder of a fantastic company called Creately) then split the 350 delegates into groups and asked them to workshop the potential role of geo-social tools and crowdsourcing approaches in addressing one of Sri Lanka’s major health crises: the recent upsurge of dengue fever infections throughout the country.

The responses of the delegates to the dengue fever epidemic provides a few key lessons and questions for NGOs and donor agencies looking to leverage mobile and social networks to support reconciliation efforts and development initiatives in countries transitioning from civil conflict.

Coalition building and feedback loops are key

Experiences from crowdsourcing operations in Kenya, Haiti and more recently Libya have shown that it’s not enough to simply collect information about the situation on the ground. If technology tools are to enhance development and humanitarian interventions in the slightest, this data needs to be properly analyzed, its meaning widely disseminated through effective public campaigns and resources mobilized by relevant actors to redress the issue or problem.

The need for a firm feedback loop between information collection and change agents, especially in post-conflict settings, was hammered home in the dengue fever workshop. The participants focused not only on collecting and mapping info on the spread of the disease, but also on the need to address much broader challenges of social norms around water maintenance through public campaigns and institutional change.

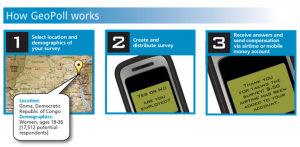

With these objectives in mind, a two-stage strategy of coalition building and campaigning emerged, each part of which was enhanced by deployment of mobile-based and social mobilisation tools. The first stage would be to accurately determine the extent of dengue fever within Sri Lanka. Some delegates proposed partnering with one of Sri Lanka’s major mobile network operators (eg, Dialog or Mobitel) to conduct a mobile survey using tools such as GeoPoll to determine prevalence of dengue fever and access to treatment centers. Others saw a SMS short-code service such as the 4646 service, which was used after the Haiti earthquake in 2010 to report needs, as the best means of collecting info.

Participants generally agreed that regardless of data collection method, the purpose of aggregating this data would ultimately be to visualise it spatially using mapping tools such as Ushahidi. Being able to physically see collected info on where dengue fever is prevalent, determine the specific location of stagnant ponds and identify districts where misconceptions about symptoms and treatment of the tropical disease are common was seen as vital to targeting of SLU efforts.

The second phase would thus be a large-scale and targeted public information and dengue fever eradication campaign, in collaboration with various NGOs, private sector operators and relevant government departments and Ministries, using this mapped, crowdsourced data.

Hugely creative ideas for the awareness-raising phase of the campaign were proposed, with suggestions ranging from YouTube clips and cross-country walks to online courses and mobile games educating users about the causes and preventative measures associated with dengue fever.

Deploying SLUs high-school chapters to run educational workshops in local communities and partner with medical NGOs, the private sector and relevant government departments to eradicate stagnant ponds in their local neighbourhood was also proposed.

Rather than simply creating a shopping list of ‘cool’ technologies and apps that could help SLU outreach, the participants therefore conceived of the avenues of information collection and popular participation offered by mobile technologies in an institutional context in which change agents (eg. civil society actors, the private sector and government agencies) must partner to create feedback loops capable of taking substantive action.

Common issues cultivate common identities

Creating new mechanisms of accountability should be central for all social change initiatives or interventions deploying technology tools. But underpinning this integrated thinking in Sri Lanka is a larger observation about the nature of reconciliation in post-conflict societies.

In many ethnically, religiously and linguistically diverse countries recovering from bloody and divisive civil conflict, distrust between communal groups often continues to pervade inter-group relations for years after the end of formal hostilities.

These perceptions and ties can come to permeate and intermediate the social and economic interactions of everyday life, in many cases being manipulated by political candidates in close contests to catalyse voters- often violently- at local, state and national elections. The repeated paroxysms of Hindu-Muslim violence in India are just some disturbing examples.

Electoral and party regulations that incentivise (or require) inclusion of all regional and communal groups into political campaigns and agendas are vital, as is sharing of power through inclusion of minority groups in cabinets and various forms of decentralisation. However, research on civil society and peacebuilding by Ashutosh Varshney has also shown that it is the relationships and trust developed between individuals of ethno-communal groups which are vital to preventing minor scuffles or even false rumours about other ethnic groups from taking on a communal nature and escalating into all-out ethno-religious warfare.

Sri Lanka Unites’ recent ‘S.H.O.W You Care: Stop Harassment Against Women’ campaign is a fantastic example of the kind of local campaign that can help build trust between communities and be enhanced by tech tools. Across the country, more than 300 young men involved in SLUs high-school chapters boarded over 1250 buses in Colombo district to inform women of their avenues of redress and encourage passengers to intervene when they see incidences of violence.

The campaign received widespread media attention. But the merits of ‘S.H.O.W,’ and even the potential dengue fever project developed in our workshop cannot be assessed solely on how they change attitudes and behavior towards gender-based violence or eradicate dengue fever.

Just as important is how large-scale campaigns such as these can foster new relational ties and trust between individuals and organizations of diverse ethnic and religious groups, creating popular consciousness of issues which cut across various individual identities and require action on an equitable basis- regardless of ethnic or religious backgrounds.

Put tech in its rightful place

So what role can mobile phones play in reconciliation? TechChange’s own Greg Maly recently observed that 90 percent of the social impact created by technology-enhanced development initiatives are the result of feedback loops created by people (or ‘the crowd’) partnering with various organizations and institutional actors to improve service delivery and solve collective problems through public campaigns or grass-roots action.

The workshops on dengue fever in Sri Lanka demonstrated how true that observation is in divided societies transitioning from conflict. Ultimately, even when campaigns such as SHOW or the proposed dengue fever eradication campaign prove only partly effective in achieving their immediate objectives, it’s vital to remember the importance of large-scale, public-interest campaigns and other regular avenues of cross-communal collaboration in reframing notions of identity and slowly re-building trust between deeply divided communities.

Mobile and social tools provide new avenues for information collection, political participation and communication that can assist in establishing ties and building trust. But their utility for reconciliation is dependent in the end on the values and expertise of coalition partners and the technology-enhanced feedback loops of institutional change they help to form.