In the last decade, social media has spread quickly across the world and has grown not just in terms of number of users on popular platforms, but also in terms of new niche platforms tailored for specific populations.

With Facebook’s 1 billion active users, the 500 million tweets that flood the Internet daily via Twitter, and the 6 billion hours of YouTube videos available online, it is clear that social media has been integrated into the daily digital lives of many people globally. Combine that with the fact that 85% of the world’s population has access to the Internet – and to many of these social networks – and you’ll find a tool that has revolutionized the way groups around the globe interact with each other.

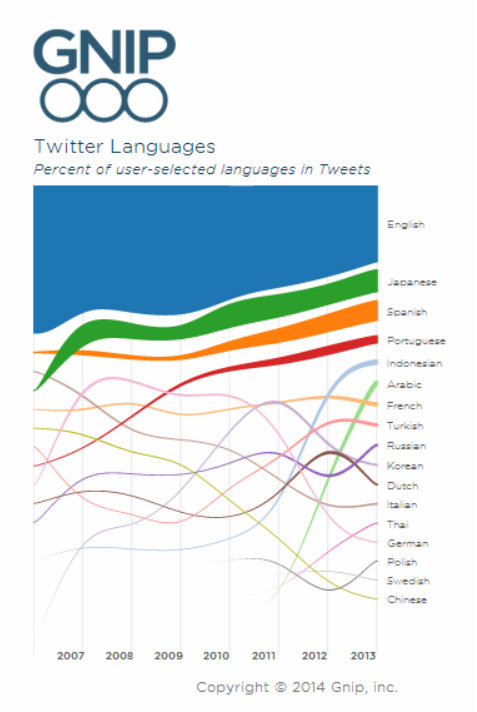

As popular as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube are, the diversity of social media platforms and the way people interact on these platforms are as diverse as the different cultures of these users. According to the social media API aggregation company, GNIP, 49% of tweets in 2013 were in a language other than English. Facebook is also available in several dozen languages.

Source: GNIP / New York Times

This “World Map of Social Networks” from Vincos.it shows how the dominant social media sites have changed since 2009.

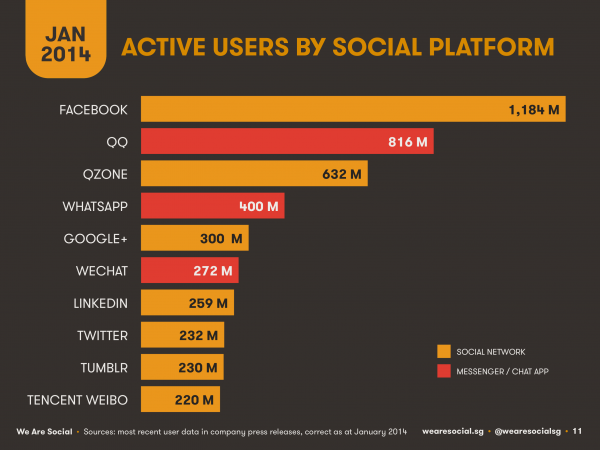

Facebook has clearly become a global leader, but its prominence can be deceptive – many more country-specific social networks have grown rapidly with extremely active user bases. In countries like China, where Facebook and Twitter are banned, sites like RenRen and Weibo, which have similar user interfaces and features, have sprung up. According to a recent article by Forbes magazine, Tencent, the parent company of China’s leading social media platform, is poised to overtake Facebook in terms of average monthly users.

Source: We Are Social / MediaBistro.com

Alternative social networks are also popular in countries in which Facebook is legal. ZingMe, for example, is extremely popular in Vietnam among teenagers and young adults and Yookos is an emerging network in southern and sub-saharan Africa; the amount of existing social media platforms worldwide is in the thousands.

Social media is designed to bring people together in different ways; it connects governments and organizations with the public and allows for the diffusion of information across the world quickly and efficiently. The limits of social media and its uses are still being defined; issues such as privacy and freedom of speech – and the lack thereof – have been repeatedly debated around the world.

We can neither confirm nor deny that this is our first tweet.

— CIA (@CIA) June 6, 2014

If social media is used differently across the world, what does this mean for social media campaigns for social causes? How do we know what the best tools are to use for targeting specific audiences? Defining and understanding who your target audience is is one of the first steps of designing an effective social change campaign. The ever-evolving social media landscape will be important to understand in order to communicate the right messages, on the right platform, for the right people, and in the right way, to be effective.

How is social media used in your country? Let us know in the comment section below or tweet us @TechChange.

Check out some of the additional resources we’ve come across that visualize the global diversity of social media:

- How the World Consumes Social Media (Mashable)

- Global Internet, Mobile and Social Media Engagement and Usage Stats and Facts [INFOGRAPHIC] (Social Media Today)

- How Africa Tweets (Portland Communications / Afritorial)

Come and join us in our discussion about the global diversity of social media and more in our upcoming Social Media for Social Change online course, which begins this Monday!

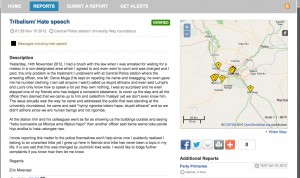

What communication technology and social media does is provide more individuals with the ability to tell a story. These stories may be the same as the official account, or may deviate jarringly and in ways that make understanding the motivations of those involved in the fighting (or civilians trying to survive) harder to decipher. In this space we see a key different between social media and communication technology in a disaster versus a conflict zone, and making the most of the technology requires recognizing this difference: in a disaster we use technology to respond to the situation, in a conflict we have to use it to understand the situation. While the volume of stories can seem overwhelming if we can learn to listen more efficiently to the information from those we wish to help their stories can start to inform and increase the effectiveness of our peacebuilding efforts.

What communication technology and social media does is provide more individuals with the ability to tell a story. These stories may be the same as the official account, or may deviate jarringly and in ways that make understanding the motivations of those involved in the fighting (or civilians trying to survive) harder to decipher. In this space we see a key different between social media and communication technology in a disaster versus a conflict zone, and making the most of the technology requires recognizing this difference: in a disaster we use technology to respond to the situation, in a conflict we have to use it to understand the situation. While the volume of stories can seem overwhelming if we can learn to listen more efficiently to the information from those we wish to help their stories can start to inform and increase the effectiveness of our peacebuilding efforts.