PreMAND field workers testing data collection tablets in Navrongo, Ghana (Photo: N. Smith)

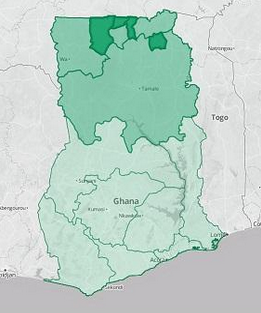

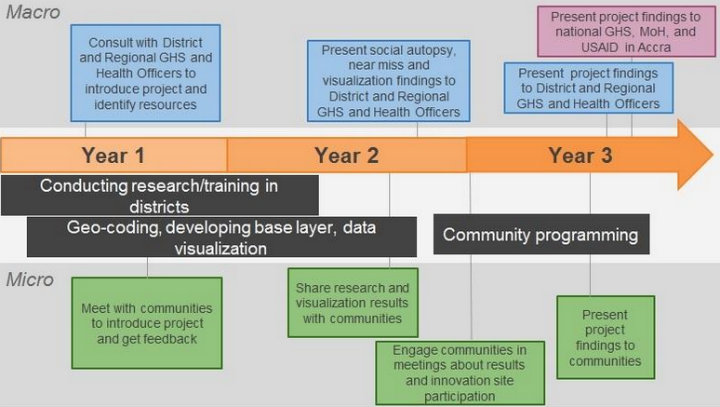

Mira Gupta, one of the star alumna of our courses on Mapping for International Development and Technology for Monitoring & Evaluation (M&E), is a Senior Research Specialist at the University of Michigan Medical School (UMMS). Last October, USAID awarded UMMS $1.44 million to assess maternal and neonatal mortality in northern Ghana. This 36-month project, “Preventing Maternal and Neonatal Mortality in Rural Northern Ghana” (also referred to as PreMAND: Preventing Maternal and Neonatal Deaths) will help USAID, the Ghana Health Service, and the Ghana Ministry of Health design interventions to prevent maternal and neonatal mortality by investigating the social, cultural and behavioral determinants of such deaths across four districts in northern Ghana. For this project, UMMS will be partnering with the Navrongo Health Research Centre and Development Seed.

We sat down with Mira to learn more about this project and how her TechChange trainings in digital mapping and technology for M&E gave her the skills and background she needed to develop her team’s project in Ghana.

1. What interested you in taking the Mapping for International Development and the Tech for M&E online courses?

I was in the process of trying to learn everything I could about our GIS options when I heard about TechChange’s Mapping for International Development course. It provided a fantastic introduction to the range of approaches being used on international development projects and the variety of organizations working in that space. The course material helped me identify which types of visualizations would be most appropriate for my team’s research. I especially benefited from the many sectors represented in the TechChange sessions because while I was trying to create a project for the Health sector, I actually learn best through a Democracy and Governance framework given my previous background in this field. TechChange provided access to mapping specialists in both areas through its instructors and other class participants.

Just as I heard of the mapping course right as I needed it, the same thing happened again with the Technology for M&E course, which I took a year later. By that point, the PreMAND project had just been awarded and I learned that I would be responsible for the evaluation components. I was excited to take the TechChange course because I knew it would provide a great overview of the many different tools being used, and that I would benefit immensely from the participation of classmates working on projects in similar settings. As expected, the content presented was incredibly valuable in informing our project approach in terms of our field data collection, methods of analysis, and presentation of findings.

2. How did the mapping component of this USAID-funded project come together?

While working on a maternal and neonatal health qualitative study a couple of years ago, I sensed that there were themes and patterns in the data that were difficult to verify since the locations of the respondents had not been geocoded. Some of the variables indicated 50/50 probabilities of any particular outcome, which seemed to suggest that there was no pattern whatsoever when viewed as a large dataset. Because my background is in Democracy and Governance, I used election maps to illustrate to my research team that once geocoded there might in fact be very distinct geographical trends in the data, drawing parallels to the locational breakdown of political party support in the United States.

I was in the process of researching mapping resources when I first heard about the TechChange’s Mapping for International Development course, and through the course I met some of the mapping experts that ultimately served as key resources in the development of our project strategy. The course gave me the necessary base knowledge to effectively liaise between our health researchers and the mapping experts to determine the best approach to meet our data visualization needs. We were extremely fortunate to have USAID-Ghana release a call for outside-the-box submissions under its Innovate for Health mechanism, right as we were developing our program concept.

3. What are the biggest challenges you anticipate in undertaking this project?

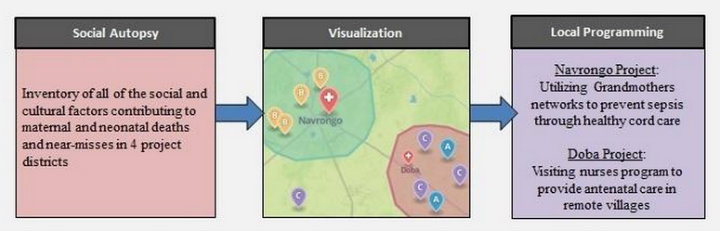

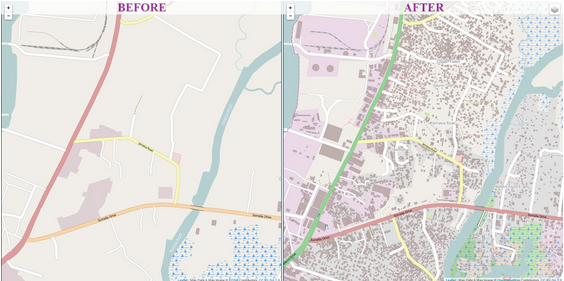

For the visualization component, generating the base layer maps will be more difficult than we originally anticipated. The various pieces of data we need are spread throughout different government sources such as the Ghana Statistical Service, the Lands Commission, and the Ministry of Roads and Highways. We will need to consult with each of these groups (and likely many others), to explore whether or not they will allow their data to be used by our project. It will require some agility on our part, as we need to stay flexible enough so that we collect any outstanding geographic data we may need through our team of field workers. While there are many moving pieces at the moment, it’s exciting for us to think that we’re building what may be the most comprehensive geographic base layer map of the region, as an initial step in developing our health indicator analysis tool.

There are also a handful of challenges related to evaluation. The primary purpose of our project is to provide new information to clarify the roles of social and cultural factors in determining maternal and neonatal deaths, and shed light on a valuable set of drivers which up until now have been unclear. We are currently in the process of finalizing our M&E framework, which has been a complex process because our project doesn’t fit the mold that most performance indicators are designed for. As a result we’ve been carefully drafting our own custom indicators through which we’ll measure our project’s progress and impact.

One of our most interesting evaluation challenges has been the development of our Environmental Mitigation and Monitoring Plan, which is traditionally intended as a tool for implementing partners to take stock of the impacts their work could have on the natural environment. In our case, we’re using it as a tool to think through our ethical approach to the potential impact of our project on the social and cultural landscape, given the challenges associated with collecting very sensitive health information and the need for data privacy. It’s pushing our team to think through every step of our project from the perspective of our various stakeholders, and has yielded many valuable insights that have strengthened our program approach.

4. What are the tools that you became familiar with in Mapping for International Development and M&E and plan on using in this project and how will you apply them to your project?

I came into Mapping for International Development knowing very little about the resources available in that space. Several of the tools that I became familiar with through the class, such as OpenStreetMap, MapBox and QGIS were highly applicable to our project in Ghana. After participating in the session led by Democracy International and Development Seed, I reached out to those instructors for their input on how I could best translate my project concept into actionable steps.

The visualizations I hoped to create were complex enough that I soon realized it would make the most sense for our research team to work directly with a mapping firm. We were so impressed by the technical feedback and past projects of Development Seed that we established a formal partnership with them and worked together to refine the vision for the project that was ultimately funded. TechChange’s training gave me the knowledge I needed to select the right partner and understand how best to combine our research goals with the available mapping resources to maximize our project’s impact.

In Technology for M&E I learned about the capabilities of different devices, survey apps—those able to capture geodata were of particular interest to me—and even project management tools. There were many helpful conversations both in the class sessions as well as in the participant-led threads around the data collection process, data privacy, and the ways in which project findings can be best communicated to a variety of stakeholder groups. What I found to be most relevant and applicable to our Ghana project were the conversations surrounding human-centered design, and the use of rich qualitative data. I gained a lot from the session led by Marc Maxson of GlobalGiving, who discussed which forms of data are the richest and easiest to interpret. The University of Michigan and our partner the Navrongo Health Research Centre already excel in qualitative data collection techniques, but the conversations throughout the TechChange M&E course inspired some new ideas as to how we might incorporate multimedia such as video and photographs in our qualitative data collection process to make our project deliverables that much more substantive.

5. What is your advice for researchers working to integrate more data visualization and mapping in their research and project interventions?

My advice would be to focus on the end user of your data and identify their needs and interests early in the process. That clarity can then be used to inform 1) what content will be most useful, and 2) what presentation format(s) will be most effective. It’s important to do some form of a needs assessment and let stakeholder feedback guide the project’s design.

In the case of our Ghana project, we are implementing a two-prong approach to our visualizations because both the government representatives and our donor will find an interactive web application most useful, while local community members in the rural North will benefit more from group discussions centered around printed maps.

It is common to sometimes present health indicator data solely as points on a map, but we are designing our visualizations to be much more detailed with background layers including health facilities, schools, compounds and roads so that those viewing the health indicator data can orient themselves a bit better to the local context. Had our end-users only been the leaders of those individual communities such detailed maps may not have been necessary. Similarly, the visualizations for one stakeholder group might incorporate a lot of words or even narrative stories based on their level of education, while for other stakeholders, those visualizations will be more image-based and we’ll orient them to the maps through presentations in their local communities.

About Mira Gupta

Mira Gupta is a Senior Research Specialist at the University of Michigan Medical School (UMMS), where she focuses on program design, strategy and evaluation. She has developed successful international aid projects in 18 countries, including 13 in Africa. Mira began her career in the Democracy and Governance sector where she worked for organizations such as IFES, the National Democratic Institute, and the Carter Center. She also developed projects in the Economic Risk and Conflict Mitigation sectors before transitioning into Global Health. Her research on the effects of local power dynamics on health-seeking behavior in northern Ghana is published the current edition of Global Public Health.