Filming of Malaria Consortium staff doctor counselling a client on proper treatment of malaria. Uganda. (Photo credit: Maddy Marasciulo-Rice, Malaria Consortium)

Malaria in Context

There is an undeniable malaria problem in the world today. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) in March 2014, half of the world’s population is at-risk, hundreds of millions of cases are reported each year, and hundreds of thousands die annually of this disease. Around 90% of these cases occur in Africa, with children under 5 years old making up the largest demographic affected.

The burden of this disease on the health care systems of developing countries is immense: Uganda has the highest malaria incidence rate in the world with 478 cases per 1,000 population per year. Fully half of inpatient pediatric deaths in Uganda are caused by this disease and in Nigeria, the most populous African country, 97% of the population is at risk.

(Source: WHO 2013 Global Malaria Report)

How are the countries of Uganda and Nigeria addressing malaria?

While both Uganda and Nigeria have national malaria control and elimination programs, due to long waiting periods and frequent stock outs of the appropriate medications at local health facilities, individuals prefer to go to private clinics, pharmacies and local drug shops to solve their health needs. When these pharmacists―often untrained in accurately diagnosing febrile illnesses―see a client complaining of fever, they often presumptively prescribe antimalarial medicines. The reverse scenario is also a common problem: pharmacists do not always give out artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACTs) when it is actually needed.

Pharmacists in Uganda assist customers with recommending antimalarial medications (Photo credit: Maddy Marasciulo-Rice, Malaria Consortium)

Presumptive treatment ― the overuse of antimalarials greatly increases the chances that malaria parasite resistance will develop and spread. In the future we might have one less weapon in our arsenal against these parasites. This overuse also means that the medicine is put over

How can rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) help treat malaria?

Fortunately, rapid diagnostic tests, or RDTs, allow malaria to be diagnosed quickly, accurately, and cheaply, using only a drop of blood and a few drops of a solution. The problem is―there is no official quality control within the private healthcare sector―the pharmacists who provide the RDT to the patient have no way to choose a good RDT from the many options on the market and the wrong choice could lead to inaccurate diagnosis. Furthermore, many of the RDT sales representatives haven’t been trained to properly explain their product to their clients.

Challenges of RDT Training for Malaria in Uganda and Nigeria

RDTs to test for malaria and drugs to treat the disease are currently available in the private healthcare sector. However, there are several challenges to scaling up RDTs in this sector in Uganda and Nigeria.

1. Lack of training with Rapid Diagnostic Testing Materials

The primary barrier to appropriate care is the lack of training among pharmacists and RDT sales providers about how to use the test and interpret the results correctly to effectively diagnose and treat a range of febrile illnesses.

Malaria Consortium, based in the UK, is one of the world’s leading non-profit organizations specializing in the prevention, control, and treatment of malaria and other tropical diseases. Their projects can be found across twelve countries in Africa and Southeast Asia. The organization strives to find effective and sustainable ways to control and manage malaria through research, implementation, and policy development. They came up with the design for a plan that could greatly help manage the disease in both Nigeria and Uganda:

If the RDT sales representatives and RDT providers can be trained to correctly use the RDTs and recognize the symptoms associated not only with malaria but with other common illnesses, then the burden of misdiagnosis and mistreatment can be greatly reduced. Furthermore, as the sales representatives travel and frequently interact with providers, they can act as trainers and further disseminate the knowledge and skills necessary to accurately diagnose and treat these diseases.

2. Prohibitively high costs

The costs associated with arranging such a training are enormous―between transporting the students and teachers to a centralized location, renting a venue, arranging lodging, and coordinating a schedule, the budget for a large-scale training would quickly be out of control. Additionally, pharmacy owners and other stakeholders working in the private sector would most likely have to assume a loss of revenue during their time away from their business while at a training.

3. Technical limitations

An eLearning platform is much more ideal for these circumstances―it’s flexible, participants don’t need to travel far, you need fewer instructors, and the information can be processed at the student’s pace and repeated when necessary. The information is also standardized and consistent, which means that a large number of people can benefit from a high quality training experience.

But how do you deliver an eLearning course when your audience has intermittent power and whose computers are not only often out-of-date, but lack the RAM, bandwidth, and software standards that such hi-tech learning platforms have come to expect?

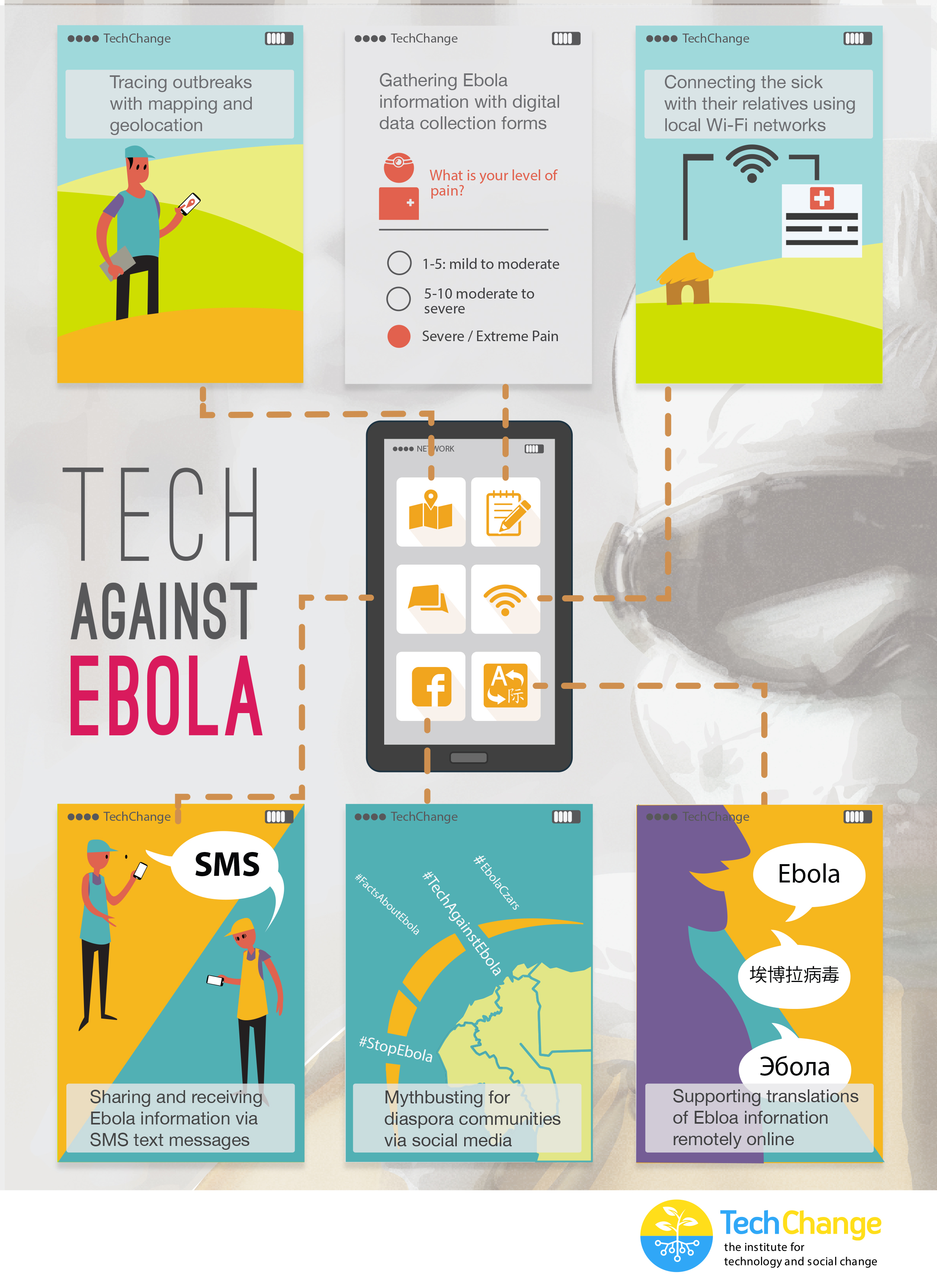

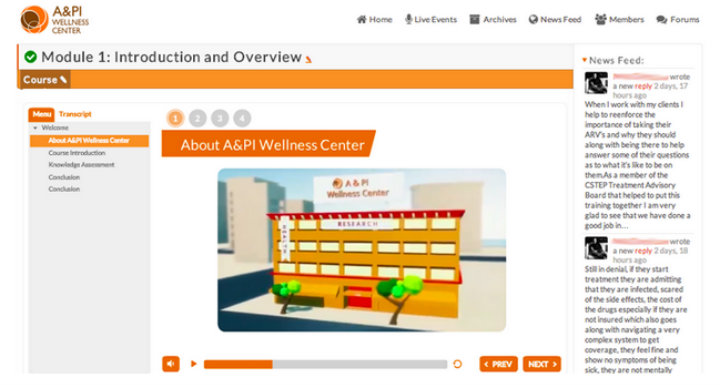

eLearning Solutions for Reaching 3000+ Healthcare Providers for Malaria

Malaria Consortium partnered with TechChange to build a comprehensive digital course to train private sector health workers and RDT sales representatives in this context. This 11 module course includes around 400 slides for 6 hours of content takes participants through the biology behind the malaria parasite, discusses the medical philosophy behind diagnostic practices, and walks users through interactive scenarios for patients presenting a range of symptoms.

Sales representatives and drug store owners in Uganda testing eLearning modules designed by TechChange and Malaria Consortium on rapid diagnostic testing for malaria. (Photo credit: Catherine Shen, TechChange)

1. Offline access and Ease of Use

Despite significant benefits such as flexibility and scalability, e-learning courses also face challenges in the developing world. Lack of sufficient internet bandwidth, reliable computers, and computer skills can pose major barriers to a training’s effectiveness.

To troubleshoot the technical issues, this course is designed to require nothing more than a computer and headphones – it comes preloaded onto USB drives so not even an Internet connection is necessary, allowing health workers in even the most rural areas to access this training. A computer tutorial is also included for health workers with little to no prior experience with computers. Our tech team is also devoted to helping solve any other technical issues that arise due to out-of-date software and hardware malfunctions, working as a remote IT team as Malaria Consortium rolls out the project.

2. Localized content

In addition to including the relevant national laws, case studies, and local examples, the narration features Nigerian and Ugandan voice actors, art, and scenarios to make the training as culturally-relevant as possible.

3. Hybrid learning

Only one part of the training won’t be computer-based; participants will still practice actually conducting the RDT tests in a face-to-face session before they begin pricking patient’s fingers for diagnosis.

The course is designed to reach upwards of 3,000 healthcare providers in the two countries and build their capacity to effectively serve their community’s needs. We look forward to seeing the impact of this training in improving quality of care in Uganda and Nigeria hopefully in the near future.

To learn more about TechChange’s custom training solutions, please contact us at info@techchange.org.

Emily Fruchterman, Catherine Shen, & Charlie Weems contributed to this post.