If you’re interested in learning more about how technology can support peacebuilding and conflict management programming, check out TC109: Technology for Conflict Management and Peacebuilding, being taught by TechChange’s Director of Conflict Management and Peacebuilding Programs, Charles Martin-Shields!

Social technology has captured the interest of emergency responders, peacebuilders, and policy makers due to the positive role it has played in disaster response in Haiti, peace promotion in Kenya, social revolution across the Middle East. In ways that differ from disaster response, though, the politics and narratives of violent conflict demand a more nuanced, risk-averse approach to bringing high-volume communication technologies to the peace making space, especially in kinetic environments.

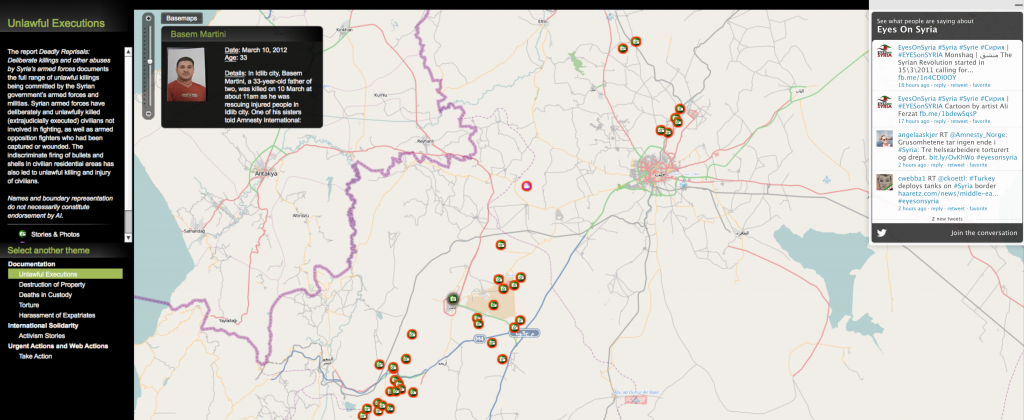

Emergent technologies such as mobile phones, social media and open-source mapping have had dramatic positive effects on emergency response since Ushahidi was first launched as part of the response to the Haiti earthquake in 2010. While the emergency response community has embraced these technologies (more or less), the peacebuilding and conflict management communities have been more circumspect. While there are good reasons for this, at some point a healthy skepticism of these technologies must give way to well thought out integration. So how do peacemakers in both large organizations and small NGOs do this, given all the political and socio-economic pitfalls waiting in the conflict and post-conflict space? What’s a lower risk way that small NGOs and individuals can be instrumental in gathering information that can be useful to large organizations like the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations?

To answer this question we can look to the way that narratives and information evolve in multidimensional peacebuilding contexts. The days of peacekeepers demarcating an agreed upon line between two parties are over – peace is being built in the middle of ongoing warfare, which means providing humanitarian aid, supporting economic development, and building political structures the can (ostensibly) represent citizens. The information we need to do this can’t just come from satellites, closed-source intelligence and surveillance systems. Virginia Page Fortna notes the importance of what the ‘peacekept’ need and want, and we have to reach out to them using channels they have access to. Even in the hardest conflict zone, people have mobile phones to send SMS messages, they tweet, and they build live digital maps to track events. This isn’t a replacement for classic closed source technology, it’s a supplement to make sure peacekeepers know what is on their host community’s mind, what people need, and their sentiments about the social and political space.

What communication technology and social media does is provide more individuals with the ability to tell a story. These stories may be the same as the official account, or may deviate jarringly and in ways that make understanding the motivations of those involved in the fighting (or civilians trying to survive) harder to decipher. In this space we see a key different between social media and communication technology in a disaster versus a conflict zone, and making the most of the technology requires recognizing this difference: in a disaster we use technology to respond to the situation, in a conflict we have to use it to understand the situation. While the volume of stories can seem overwhelming if we can learn to listen more efficiently to the information from those we wish to help their stories can start to inform and increase the effectiveness of our peacebuilding efforts.

What communication technology and social media does is provide more individuals with the ability to tell a story. These stories may be the same as the official account, or may deviate jarringly and in ways that make understanding the motivations of those involved in the fighting (or civilians trying to survive) harder to decipher. In this space we see a key different between social media and communication technology in a disaster versus a conflict zone, and making the most of the technology requires recognizing this difference: in a disaster we use technology to respond to the situation, in a conflict we have to use it to understand the situation. While the volume of stories can seem overwhelming if we can learn to listen more efficiently to the information from those we wish to help their stories can start to inform and increase the effectiveness of our peacebuilding efforts.