Cross-posted from the TC104: Global Innovations for Digital Organizing course we ran last May. If you are interested in mobile organization and censorship/privacy in the 21st century, consider enrolling in the next round in January.

Credit: Duncan 2012

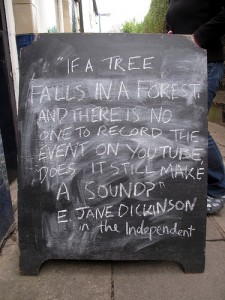

Most of you will be familiar with the philosophical thought experiment, “If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?” Well over recent weeks I’ve been mulling over the much less catchy or succinct question of “If a person tweets/updates their status/sends a text/blogs and no one responds, did they really make a sound?” It probably won’t be making it onto a philosophy syllabus anytime soon, but hear me out…

I recently travelled to Malawi to trial a social accountability approach designed to improve the quality of rural schools. The purpose was to help adolescent girls analyse their problems and provide an opportunity for them to raise these with school management to find collaborative solutions. I found it both sad and hopeful when some of the girls explained that nobody had ever asked for their opinions – they saw this as a chance to finally speak. A voice was incredibly important to these young women and self-expression seemed to have real value in itself. But I wonder if voice is enough. Doesn’t school management also need to value and respond to girls’ opinions? I kept asking: If speaking out doesn’t lead to action, do we just create false expectations and disillusionment?

During TC104 I’ve thought about this a lot. The internet and mobile phones offer so many opportunities for voice and reaching out – to other citizens but also to people in power. But I question what other elements are needed to ensure that voice leads to dialogue, and dialogue leads to responsive actions and tangible development changes.

Credit: Plan

I came to this course wanting to know about the digital tools/approaches that could support young people’s meaningful participation in social accountability initiatives (for an explanation check out pages 10-11 of Plan’s Governance Learning Guide). I was interested in how technology could leverage their voices and strengthen the interaction and responsiveness between them and their state to create better services, like health and education. As such the expert interviews with Barak Hoffman and Darko Brkan were among the most interesting for me. The Maji Matone project in Tanzania and the accountability and transparency work by Dosta! in Bosnia were excellent examples of digital media’s potential use to increase responsiveness of governments to citizens’ voices.

However, the Tanzanian example acted as a cautionary tale of how projects must recognise wider socio-political contexts in which they seek to work. That project seemed to offer a simple technology-enabled way of directly linking citizens’ voices to government action on water points. However, as this blog post explains the target communities were not used to demanding their rights to services and seemed sceptical of the government’s ability or will to respond. In addition, in a tight-knit local community people were scared of being seen as trouble makers and being critical of those in power. As a result they saw little benefit, and indeed some risk, in exercising their voice through the ICT channels that were offered.

Credit: Plan

In contrast Darko’s post explains the approaches used by Dosta! to first strengthen a weak Bosnian civil society. What interests me most, though, are Dosta!’s tactics to encourage responsiveness from the supply side through mixing digital and traditional tools for accountability. They were able to leverage power over politicians through the tangible threat of removal through democratic elections and in 2006 discredited the Prime Minister by exposing his corruption through the media. It was the media which again played a strong role in promoting the fact-checking website Istinomjer with further impact on election discourse. This active media environment and electoral accountability gives additional power to digital information and can help turn transparency into action.

These examples underline that creating opportunities for voice and participation doesn’t automatically lead to accountability and tangible changes. A whole host of reasons may stop citizens raising their voices or governments from answering – a key one being lack of effective digital and traditional feedback loops. The workshops from Dhairya and Rob provided lots of ideas for integrating technology into our social accountability projects and I’m excited to share these with colleagues and get to work. But the Maji Matone example reminds me not to lose sight of the need to analyse existing communication, political and social environments before getting too carried away with the technology.

Jennifer Doherty is a Governance Programme Officer working in the Programme Support and Impact Unit of Plan UK, an international development charity promoting the rights of children.