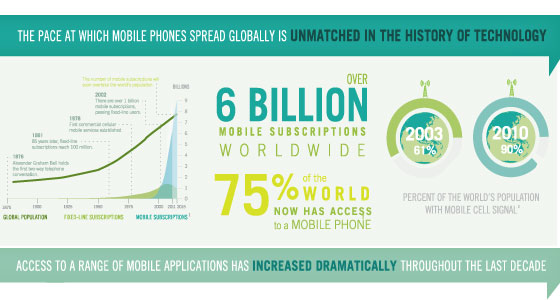

[Maximizing Mobile Infographic. Source: World Bank]

This is a guest post by ![]() Joellen Raderstorf, a participant in the TechChange course: TC105: Mobiles for International Development. You can follow Joellen on Twitter: @actingupmama

Joellen Raderstorf, a participant in the TechChange course: TC105: Mobiles for International Development. You can follow Joellen on Twitter: @actingupmama

How many people have had the experience of telling people you are studying ICTD or working in the field of ICTD to watch their eyes glaze over. How do you explain ICTD to a friend in the grocery line, your grandmother at a family reunion, or your father who thinks technology is ruining young people?

Most commonly, ICTD is described as an attempt to bridge the digital divide—the disparity between the ‘haves’ and ‘have-nots’ in the technological world. Some consider it to be the latest golden bullet—with access to technology comes the ability to improve a livelihood. A farmer can access commodity information in Cameroon to ensure a fair price and expand reach beyond the local market. A family living in a rural community, who once found doctors out of reach, can significantly improve the chances of a child surviving past the age of 5 due to a community health worker equipped with a mobile health application connecting to doctors real time. A child can grow up with access to education and the opportunity to take college courses without great expense or the necessity of leaving her community.

Alternatively, perhaps a less altruistic view of ICTD depicts the field as a marriage between telecom companies in search of expanding markets and NGOs in need of new solutions to addressing hunger and poverty. The proliferation of the mobile phone in the developing world has been nothing short of a technological revolution according to the World Bank. Powerful infographics from the World Bank and USAID depict an undeniable success story regardless of the original intention. On a planet of 7 billion, there are over 6 billion mobile subscriptions and over 75% of the world has access to a mobile phone. Besides providing a link to markets, education and health providers, mobile technology is employed to create a safer and less corrupt world. Of course ensuring the bandwidth to handle the mobile data traffic expected to reach 1.2 GB per user by 2016 will present a challenge to the FCCs of the world and a subject for a future blog post.

One last point of interest in the world of ICTD identity is confusion around the acronym. ICTD is often interchanged with ICT4D, a nuance on the surface, but politically charged when peering more deeply. What implications are being asserted when one says ICT for development? Some suggest this is another version of colonialism. Terminology does evolve over time and development lingo could certainly use an overhaul, perhaps alleviating the need to define what ICTD means to everyone. For an in-depth definition, refer to the Wikipedia page for ICT4D where some (or one) ICTDers have been doing a commendable job educating the world about this enigmatic field.