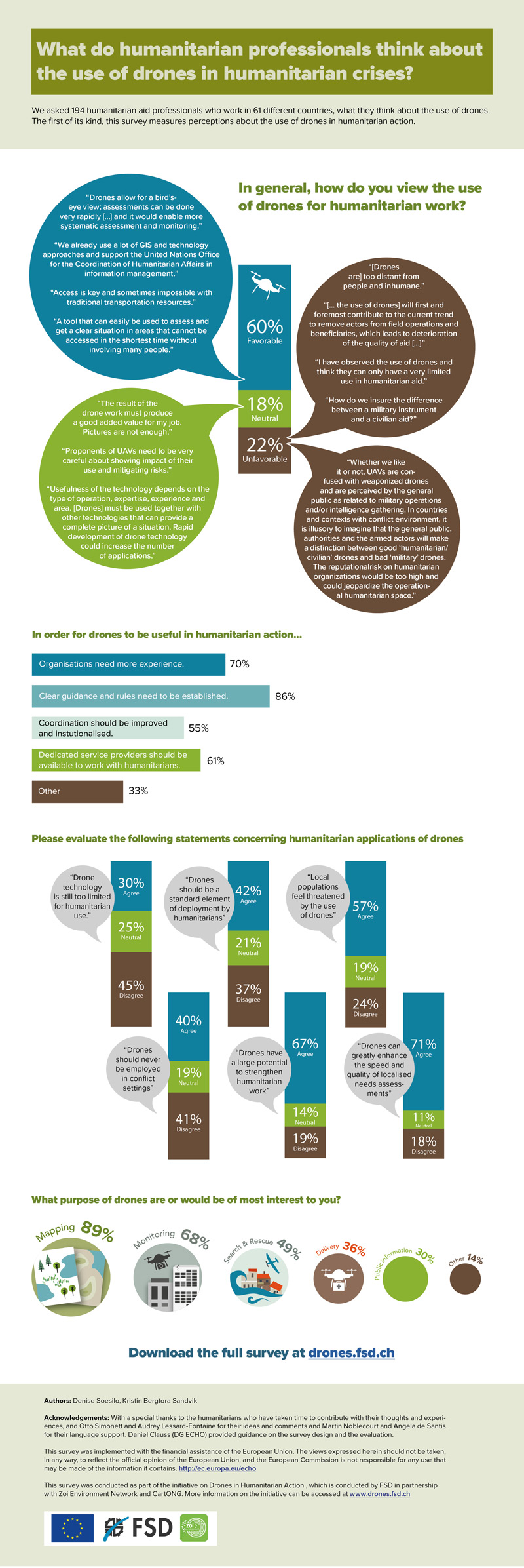

Drones are one of the most controversial technologies in disaster response operations. To find out what exactly humanitarian aid workers think about the use of these unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV), the Swiss Foundation for Mine Action (FSD) with funding from EU Humanitarian Aid has now published a survey. In total, close to 200 disaster responders working in 61 different countries took part in what is the first comprehensive survey of how humanitarian professional view drones.

The survey shows that a substantial majority of respondents (60%) believe that drones can have a positive impact in disaster response operations, while only less than a quarter (22%) see their use negatively – at least when used following natural disasters. The opinions shift significantly, when asking about use of drones in conflict zones. Here, humanitarian workers are sharply split: while 40% stated that drones should never be used by humanitarian organisations in conflict settings, 41% said they would consider using drones even during armed conflicts.

Interestingly, a majority (57%) said that they believe that the local populations feel threatened by drones – even in non-conflict environments. However, this perception is not backed up with the experience that FSD has gathered as part of the EU Humanitarian Aid funded initiative “Fostering the Appropriate Use of Air-Borne Systems in Humanitarian Crisis” so far. As part of that initiative, FSD, in partnership with the Zoi Environment Network and CartONG, is currently collecting 16 case studies ranging from mapping, to de-mining to transporting medical samples. Nine of these case studies have already been published and can be found here.

Most survey respondents saw a very real potential for drones to assist in humanitarian response operations, particularly in situations where drones can be used to create maps, monitor activities, support search and rescue operations or deliver cargo. However, humanitarian workers also stressed that drones need to be able to provide a real added value compared to existing technologies.

The survey also showed that much more needs to be done within the humanitarian sector to build knowledge about the advantages, disadvantages, capabilities and limitations of drones. The vast majority (87%) of respondents said that they did not have first-hand knowledge of using drones. Many of them explained that they were looking for guidance and needed experience to make the best use of the technology.

As drones become more affordable and widespread, there is no question that UAVs will become more and more common in disaster zones. The results of this survey show that more needs to be done to better understand the added value of drones and to provide humanitarian organisations with practical guidance on how and where drones should be used.

Key figures of the survey are summarised in the infographic below. The complete survey can be downloaded here.

This piece originally appears on the FSD Blog. All images courtesy of FSD.