There has been much buzz recently in the social media community about a recent article published in The New Yorker magazine titled “Small Media” by Malcolm Gladwell. Gladwell questions whether, despite creating greater awareness and arguably greater access, social media has ultimately hijacked more traditional forms of public activism such as protests and gatherings? Gladwell’s point should not easily be dismissed, even if one is inclined to disagree with him, but rather considered critically. This question about the value of social media is one I have been struggling with myself. However, after attending a panel discussion this month featuring Rebecca Byerly, the only foreign journalist based in Indian controlled Kashmir, about extreme violence this past summer – I gained some clarity and maybe those who sympathize with Gladwell can as well.

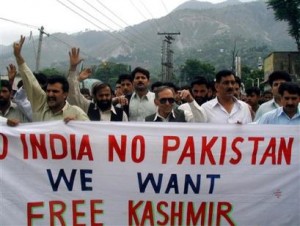

Consider Jammu-Kashmir: a disputed territory on the cusp of India and Pakistan that has, for the past sixty years, been marred by violent revolt, calls for independence and political power plays between hostile neighbors. At the heart of the conflict, however, is human suffering that has gone on too long and the bloodshed escalated to new heights this past summer sparked by the death of a young man killed by a stray bullet fired by Indian army officers in a football stadium. Over one hundred people have been killed in clashes between the army deployment and civilian population since June, 2010 but unlike before, when deaths and other injustices went largely undocumented or unheard of, social media is now bringing the Kashmir question much deserved national and global attention.

Consider Jammu-Kashmir: a disputed territory on the cusp of India and Pakistan that has, for the past sixty years, been marred by violent revolt, calls for independence and political power plays between hostile neighbors. At the heart of the conflict, however, is human suffering that has gone on too long and the bloodshed escalated to new heights this past summer sparked by the death of a young man killed by a stray bullet fired by Indian army officers in a football stadium. Over one hundred people have been killed in clashes between the army deployment and civilian population since June, 2010 but unlike before, when deaths and other injustices went largely undocumented or unheard of, social media is now bringing the Kashmir question much deserved national and global attention.

A new generation of tech savvy revolutionaries are reshaping the conflict and demanding a political solution, some semblance of normalcy and accountability using amateur videos recorded on cell phones, blogs, tweets, Facebook groups and online gatherings. At the same time, this spread of information allows those entrenched in the every-day struggle for peace to dispel many of the myths about Kashmir. For example, it is often assumed that the revolt is driven by unemployment, poverty and government negligence. On the contrary, Kashmir is one of the wealthier states in India but infected by mismanagement. Still, people are not as poor as in other parts of the country – especially those who are taking to the streets in protest. Frustration also rises out of paralysis bred by indefinite school shutdowns, restricted movement, political alienation of civil society and prolonged curfews. What is more, it is clear from the vociferous protests of the youth that their grievances are primarily against the Indian government and armed forces but they also don’t trust Pakistan. The federal government can no longer sweep the Kashmir issue under the rug or point the finger of blame at external actors. Social media is forcing the state to consider its role in propagating cycles of violence and violating the rights of its people.

Perhaps most importantly, however, is the role of social media in encouraging non-violent protest over violent revolt. As Byerly pointed out in her presentation, she has been surprised to learn that many of youth are choosing to embrace non-violence thanks to new technology. People are learning quickly that a video camera or cell phone can be just as powerful, if not more, for resolving conflict as any conventional weapon. There is a generational shift that should not be ignored between the adolescents of this age and their parents who were more willing to take up arms. The trend towards non-violence is encouraging but should be viewed with cautious optimism. Not all those who embrace non-violence remain non-violent. In fact, as Byerly pointed out, there are some who feel so frustrated by lack of change that not only do they return to violent means but instead of hurling sticks and stones, they now hurl grenades and rockets. Another danger in the social media revolution is that because practically anyone has access to these charged videos and images, how will they be received and what will people do with them? Just as the internet can be used to rally people together in the cause of peace, images of young men and women abused by the government mean to protect them can be distorted by some to produce greater violence. Just imagine an impressionable young man being given an image of someone his age with a bullet through his head and being told, “Look at your Muslim brother across the border and what has been done to him. What will you do about it?” The possibilities for positive repercussions are endless but so are the possibilities for negative.

Gladwell correctly writes that thanks to social media, “the traditional relationship between political authority and popular will has been upended, making it easier for the powerless to collaborate, coordinate, and give voice to their concerns.” But while face to face contact may lessen as a result of social media, the redefinition of activism does not necessarily have to translate as lessened value or impact.

In the hype and excitement over new and emerging networking technologies, I feel that sometimes we forget technology is never the goal, nor the end, of human action. Social media is merely a tool for activism, an instrument to facilitate dialogue, raise awareness and push boundaries for human progress and social change. It is therefore imperative to always keep in perspective not only how these tools can be used but why they help people do good.